چهرهى زن در شعر احمد شاملو

(متن انگلیسی)

مجيد نفيسى

این پانزدهمین و آخرین فصل از کتاب «در جستجوی شادی: در نقد فرهنگ مرگپرستی و مردسالاری در ایران»، نشر باران، سوئد، ۱۳۷۰ است. (مقدمه کتاب -- فصل اول -- فصل دوم - فصل سوم - فصل چهارم - فصل پنجم - فصل ششم - فصل هفتم - فصل هشتم - فصل نهم - فصل دهم - فصل دوازدهم)

براى بررسى چهرهى زن در شعر احمد شاملو لازم است ابتدا نظرى به پيشينيان او بيندازيم. در ادبيات كهن ما، زن حضورى غايب دارد و شايد بهترين راه براى ديدن چهرهى او پرده برداشتن از مفهوم صوفيانهى عشق باشد. مولوى عشق را به دو پارهى مانعةالجمعِ روحانى و جسمانى تقسيم مىكند. مرد صوفى بايد از لذتهاى جسمانى دستشسته تحت ولايت مرد مُرشد خانهى دل را از عشق به خدا آكنده سازد. زن در آثار او همه جا مترادف با عشق جسمانى و نفس حيوانى شمرده شده و مرد عاشق بايد وسوسهى عشق او را در خود بكشد: عشق آن زنده گزين كو باقى است.

برعكس در غزليات حافظ عشق به معشوقهى زمينى تبليغ مىشود و عشق صوفيانه فقط چون فلفل و نمكى به كار مىرود. با اين وجود عشق زمينى حافظ نيز جنبهاى غيرجسمانى دارد. مرد عاشق فقط نظرباز است و به جز از غبغب به بالاى معشوق به چيزى نظر ندارد. و زن معشوق نه فقط از جسم بلكه از هرگونه هويت فردى نيز محروم است. تازه اين زن خيالى چهرهاى ستمگر و دستى خونريز دارد و افراسيابوار كمر به قتل عاشق سياوشوش خويش مىبندد:

شاه تركان سخن مدعيان مىشنود

شرمى از مظلمه خون سياووشش باد

در واقعيت مرد ستمگر است و زن ستمكش ولى در خيال نقشها عوض مىشوند تا اين گفتهى روانشناسان ثابت شود كه ديگرآزارى آن روى سكهى خودآزارى است.

با ظهور ادبيات نو زن رخى مىنمايد و پرده تا حدى از عشق روحانى مولوى و معشوقهى خيالى حافظ برداشته مىشود. نيما در منظومهى «افسانه» به تصويرپردازى عشقى مالیخولیایی اما زمينى مىنشيند؛ عشقى كه هويتى مشخص دارد و متعلق به فرد و محيط طبيعى و اجتماعى معينى است.

چوپانزادهاى غمزده، در درههاى ديلمان نشسته و همچنان كه از درخت اَمرود و مرغ كاكلى و گُرگى كه دزديده از پس سنگى نظر مىكند ياد مىنمايد، با «افسانه» یعنی تجسم دوگانه ی دل عاشقپيشه و دلدار خود، در گفتگوست. نيما از زبان او مىگويد:

حافظا اين چه كيد و دروغىست

كز زبان مى و جام و ساقىست

نالى ار تا ابد باورم نيست

كه بر آن عشق بازى كه باقىست

من بر آن عاشقم كه رونده است

بر گسترهى همين مفهوم نوين از عشق است كه به شعرهاى عاشقانهى احمد شاملو مىرسيم. من با الهام از يادداشتى كه شاعر خود بر چاپ پنجم هواى تازه در سال ۱۳۵۵ نوشته، شعرهاى عاشقانهى او را به دو دورهى ركسانا و آيدا تقسيم مىكنم.

ركسانا يا روشنك نام دختر نجيبزادهاى سُغدى است كه اسكندر مقدونى او را به زنى خود درآورد. شاملو علاوه بر اينكه در سال ۱۳۲۹ شعر بلندى به همين نام سروده در برخى از شعرهاى ديگر هواى تازه نيز از ركسانا به نام يا بىنام ياد مىكند. او خود مىنويسد:«ركسانا، با مفهوم روشن و روشنايى كه در پس آن نهان بود نام زنى فرضى شد كه عشقش نور و رهايى و اميد است. زنى كه مىبايست دوازده سالى بگذرد تا در آيدا در آينه شكل بگيرد و واقعيت پيدا كند. چهرهاى كه در آن هنگام هدفى مهآلود است، گريزان و ديربهدست يا يكسره سيمرغ و كيميا. و همين تصوير مايوس و سرخورده است كه شعرى به همين نام را مىسازد _ يأس از دست يافتن به اين چنين همنفسى.» (صفحه ۳۴۸(

در شعر ركسانا، صحبت از مردى است كه در كنار دريا در كلبهاى چوبين زندگى مىكند و مردم او را ديوانه مىخوانند. مرد خواستار پيوستن به ركسانا روح درياست ولى ركسانا عشق او را پس مىزند:

بگذار هيچكس نداند، هيچكس نداند تا روزى كه سرانجام، آفتابى كه

بايد به چمنها و جنگلها بتابد، آب اين درياى مانع را

بخشكاند و مرا چون قايقى فرسوده به شن بنشاند و بدين

گونه، روح مرا به ركسانا ــ روح دريا و عشق و زندگى ــ باز رساند.

عاشق شكستخورده كه در ابتداى شعر چنين به تلخى از گذشته ياد كرده:

بگذار كسى نداند كه چگونه من به جاى نوازش شدن، بوسيده شدن،

گزيده شدهام!

اكنون در اواخر شعر از زبان اين زن مهآلود چنين به جمعبندى از عشق شكستخوردهى خود مىنشيند:

و هر كس آنچه را كه دوست مىدارد در بند مىگذارد

و هر زن مرواريد غلطان خود را

به زندان صندوق محبوس مىدارد

در شعر «غزل آخرين انزوا» (۱۳۳۱) بار ديگر به نوميدى فوق برمىخوريم:

عشقى به روشنى انجاميده را بر سر بازارى فرياد نكرده، منادىِ نام انسان

و تمامى دنيا چگونه بودهام؟

در شعر «غزل بزرگ» (۱۳۳۰) ركسانا به «زن مهتابى» تبديل مىشود و شاعر پس از اينكه او را پارهى دوم روح خود مىخواند نوميدانه مىگويد:

و آنطرف

در افقِ مهتابىِ ستارهبارانِ رو در رو،

زن مهتابى من ...

و شب پر آفتابِ چشمش در شعلههاى بنفشِ درد طلوع مىكند:

»_مرا به پيش خودت ببر!

سردار بزرگ رؤياهاى سپيد من!

مرا به پيش خودت ببر!«

در شعر «غزل آخرين انزوا» رابطهى شاعر با معشوقهى خياليش به رابطهى كودكى نيازمند محبت مادرى ستمگر ماننده مىشود:

چيزى عظيمتر از تمام ستارهها، تمام خدايان:

قلبِ زنى كه مرا كودكِ دستنوازِ دامنِ خود كند!

چرا كه من ديرگاهيست جزين هيبت تنهايى كه به دندانِ سردِ بيگانگىها جويده شده است نبودهام

جز منى كه از وحشت تنهايى خود فرياد كشيده است نبودهام...

نام ديگر ركسانا زن فرضى «گلكو»ست كه در برخى از شعرهاى هواى تازه به او اشاره شده. شاعر خود در توضيح كلمهى گلكو مىنويسد:»گلكو نامى است براى دختران كه تنها يك بار در يكى از روستاهاى گرگان (حدود علىآباد) شنيدهام. مىتوان پذيرفت كه گلكو باشد... همچون دختركو كه شيرازيان مىگويند، تحت تلفظى كه براى من جالب بود و در يكى دو شعر از آن بهره جستهام گلكوست. و از آن نام زنى در نظر است كه مىتواند معشوقى يا همسر دلخواهى باشد. در آن اوان فكر مىكردم كه شايد جزء «كو» در آخر اسم بدون اينكه الزاماً معنى لغوى معمولى خود را بدهد مىتواند به طور ذهنى حضور نداشتن، در دسترس نبودن صاحب نام را القا كند. (صفحه ۳۴۵(

ركسانا و گلكو هر دو زن فرضى هستند با اين تفاوت كه اولى در محيط ماليخوليايى ترسيم مىشود، حال آنكه دومى در صحنهى مبارزهى اجتماعى عرضاندام كرده به صورت «حامى» مرد انقلابى درمىآيد.

در شعر «مه» (۱۳۳۲) مىخوانيم:

در شولاى مه پنهان، به خانه مىرسم. گلكو نمىداند.

مرا ناگاه

در درگاه مىبيند.

به چشمش قطره اشكى بر لبش لبخند، خواهد گفت:

«بيابان را سراسر مه گرفته است... با خود فكر مىكردم كه مه،

گر همچنان تا صبح مىپاييد

مردان جسور از خفيهگاه خود

به ديدار عزيزان باز مىگشتند.«

مردان جسور به مبارزهى انقلابى روى مىآورند و چون آبايى معلم تركمن صحرا شهيد مىشوند و وظيفهى دخترانى چون گلكو به انتظار نشستن و صيقل دادن سلاح انتقام آبايىها شمرده مىشود. (از زخم قلب آبايى)

در شعر ديگرى به نام «براى شما كه عشقتان زندگىست» (۱۳۳۰) ما با مبارزهاى آشنا مىشويم كه بين مردان و دشمنان آنها وجود دارد و شاعر از زنان مىخواهد كه پشت جبههى مردان باشند و به آوردن و پروردن شيران نر قناعت كنند:

شما كه به وجود آوردهايد ساليان را

قرون را

و مردانى زادهايد كه نوشتهاند بر چوبهى دارها

يادگارها

و تاريخ بزرگ آينده را با اميد

در بطن كوچك خود پروردهايد.

....

و به ما آموختهايد تحمل و قدرت را در شكنجهها

و در تعصبها

چنين زنانى حتى زيبايى خود را وامدار ذوق مردان هستند:

شما كه زيباييد تا مردان

زيبايى را بستايند

و هر مرد كه به راهى مىشتابد

جادويىِ نوشخندى از شماست

و هر مرد در آزادگى خويش

به زنجير زرين عشقىست پاىبست

اگرچه زنان روح زندگى خوانده مىشوند ولى نقشآفرينان واقعى مردان هستند:

شما كه روح زندگى هستيد

و زندگى بى شما اجاقىست خاموش؛

شما كه نغمه آغوش روحتان

در گوش جان مرد فرحزاست

شما كه در سفر پرهراس زندگى، مردان را

در آغوش خويش آرامش بخشيدهايد

و شما را پرستيده است هر مرد خودپرست،

عشقتان را به ما دهيد

شما كه عشقتان زندگى است !

و خشمتان را به دشمنان ما

شما كه خشمتان مرگ است!

در شعر معروف «پريا» (۱۳۳۲) نيز زنان قصه يعنى پريان را مىبينيم كه در جنگ ميان مردان اسير با ديوان جادوگر جز خيالپردازى و ناپايدارى و بالاخره گريه و زارى كارى ندارند.

در مجموعهشعر «باغ آينه» كه پس از «هواى تازه» و قبل از «آيدا در آينه» چاپ شده شاعر را مىبينيم كه كماكان در جستجوى پارهى دوم روح و زن همزاد خود مىگردد:

من اما در زنان چيزى نمىيابم گر آن همزاد را روزى نيابم ناگهان خاموش (كيفر ۱۳۳۴)

اين جستجو عاقبت در «آيدا در آينه» به نتيجه مىرسد:

من و تو دو پارهى يك واقعيتيم (سرود پنجم)

«آيدا در آينه» را بايد نقطه اوج شعر شاملو به حساب آورد. ديگر در آن از مشقهاى نيمايى و نثرهاى رمانتيك، اثرى نيست و شاعر سبك و زبان خاص خود را به وجود آورده است. نحوهى بيان اين شعرها ساده است و از زبان فاخرى كه به سياق متون قديمى در آثار بعدى شاملو غلبه دارد چندان اثرى نيست. شاعر شور عشق تازه را سرچشمهى جديد آفرينش هنرى خود مىبيند:

نه در خيال كه روياروى مىبينم

ساليانى بارور را كه آغاز خواهم كرد.

خاطرهام كه آبستن عشقى سرشار است،

كيف مادر شدن را در خميازههاى انتظارى طولانى

مكرر مىكند.

...

تو و اشتياق پر صداقت تو

من و خانهمان

ميزى و چراغى . آرى

در مرگآورترين لحظه انتظار

زندگى را در روياهاى خويش دنبال مىگيرم؛

در روياها

و در اميدهايم!

(و همچنين نگاه كنيد به شعر «سرود آن كس كه از كوچه به خانه بازمىگردد» ، «و حسرتى» از كتاب مرثيههاى خاك كه در آن عشق آيدا را به مثابه زايشى در چهل سالگى براى خود مىداند.)

عشق به آيدا در شرايطى رخ مىدهد كه شاعر از آدمها و بويناكى دنياهاشان خسته شده و طالب پناهگاهى در عزلت است:

مرا ديگر انگيزهى سفر نيست

مرا ديگر هواى سفرى به سر نيست

قطارى كه نيمهشبان نعرهكشان از ده ما مىگذرد

آسمان مرا كوچك نمىكند

و جادهاى كه از گردهى پل مىگذرد

آرزوى مرا با خود به افقهاى ديگر نمىبرد.

آدمها و بويناكى دنياهاشان يكسر

دوزخىست در كتابى كه من آن را

لغت به لغت از بر كردهام

تا راز بلند انزوا را دريابم. (جادهى آنسوى پل)

اين عشق براى او به مثابه بازگشت از شهر به ده و از اجتماع به طبيعت است:

و آغوشت

اندك جايى براى زيستن

اندك جايى براى مردن،

و گريز از شهر كه با هزار انگشت، به وقاحت

پاكى آسمان را متهم مىكند. (آيدا در آينه)

و همچنين:

عشق ما دهكدهاى است كه هرگز به خواب نمىرود

نه به شبان و

نه به روز.

و جنبش و شور و حيات

يك دم در آن فرو نمىنشيند. (سرود پنجم)

ركسانا زن مهآلود اكنون در آيدا بدن مىيابد و چهرهاى واقعى به خود مىگيرد:

بوسههاى تو

گنجشكگان پرگوى باغند

و پستانهايت كندوى كوهستانهاست (سرود براى سپاس و پرستش)

كيستى كه من اينگونه به اعتماد

نام خود را

با تو مىگويم،

كليد خانهام را

در دستت مىگذارم،

نان شادىهايم را

با تو قسمت مىكنم،

به كنارت مىنشينم و بر زانوى تو

اينچنين آرام

به خواب مىروم؟ (سرود آشنايى)

حتى شب كه در شعرهاى گذشته (و همچنين آينده) مفهومى كنايى داشت و نشانهى اختناق بود اكنون واقعيت طبيعى خود را بازمىيابد:

تو بزرگى . مثه شب .

اگه مهتاب باشه يا نه

تو بزرگى

مثه شب

خود مهتابى تو اصلاً خود مهتابى تو

تازه وقتى بره مهتاب و

هنوز

شب تنها، بايد

راه دورى رو بره تا دم دروازهى روز،

مثه شب گود و بزرگى ، مثه شب، (من و تو، درخت و بارون...)

شيدايى به آيدا در كتاب بعدى شاملو «آيدا درخت و خنجر و خاطره» چنين به نقطهى كمال خود مىرسد:

نخست

ديرزمانى در او نگريستم

چندان كه چون نظر از وى بازگرفتم

در پيرامون من

همه چيزى

به هيئت او درآمده بود.

آنگاه دانستم كه مرا ديگر

از او

گريز نيست. (شبانه)

ولى سرانجام با بازگشت اجبارى شاعر از ده به شهر به مرحلهى آرامش خود بازمىگردد:

و دريغا بامداد

كه چنين به حسرت

درهى سبز را وانهاد و

به شهر باز آمد؛

چرا كه به عصرى چنين بزرگ

سفر را

در سفرهى نان نيز، هم بدان دشوارى به پيش مىبايد برد

كه در قلمرو نام . (شبانه)

شاملو از آن پس از انزوا بيرون مىآيد و دفترهاى جديد شعر او چون «دشنه در ديس»، «ابراهيم در آتش»، «كاشفان فروتن شوكران» و «ترانههاى كوچك غربت» توجه او را به مسايل اجتماعى و بخصوص مبارزهى مسلحانهى چريكى شهرى در سالهاى پنجاه نشان مىدهد. با وجود اينكه در اين سالها برخلاف سالهاى بيست و سى كه شعر «به شما كه عشقتان زندگىست» در آن دوران سروده شده بود زنان روشنفكر نقش مستقلى در مبارزهى اجتماعى بازى مىكنند ولى در شعرهاى شاملو از جاپاى مرضيه احمدىاسكويى در كنار احمد زيبرم اثرى نيست.

چهرهى زن در شعر شاملو به تدريج از ركسانا تا آيدا بازتر مىشود ولى هنوز نقطههاى حجاب وجود دارند. در ركسانا زن چهرهاى اثيرى و فرضى دارد و از يك هويت واقعى فردى خالى است. به عبارت ديگر شاملو هنوز در ركسانا خود را از عشق خيالى مولوى و حافظ رها نكرده و به جاى اينكه در زن انسانى با گوشت و پوست و احساس و انديشه و حقوق اجتماعى برابر با مردان ببيند، او را چون نمادى به حساب مىآورد كه نشانهى مفاهيمى كلى چون عشق و اميد و آزادى است. در آيدا چهرهى زن باز مىشود و خواننده در پسِ هيئت آيدا، انسانى با جسم و روح و هويت فردى مىبيند. در اينجا عشق يك تجربهى مشخص است و نه يك خيالپردازى صوفيانه يا ماليخولياى رمانتيك. و اين درست همان مشخصهاىست كه ادبيات مدرن را از كلاسيك جدا مىكند: توجه به «مشخص» و «فرد» به جاى «مجرد» و «نوع» و پرورش شخصيت به جاى تيپسازى . با اين همه در «آيدا در آينه» نيز ما قادر نيستيم كه به عشقى برابر و آزاد بين دو دلداده دست يابيم. شاملو در اين عشق به دنبال پناهگاهى مىگردد يا آنطور كه خود مىگويد معبدى (جاده آنسوى پل) يا مسجدى(ققنوس در باران) و آيدا فقط براى آن هويت مىيابد كه آفرينندهى اين آرامش است. شايد رابطهى فوق را بتوان متأثر از بينشى دانست كه شاملو از هنگام سرودن شعرهاى ركسانا نسبت به پيوند عاشقانهى زن و مرد داشته و هنوز هم دارد. بنابر اين نظر، دو دلداده چون دو پارهى ناقص انگاشته مىشوند كه تنها در صورت وصل مىتوانند به يك جزء كامل و واحد تبديل شوند (تعابيرى چون دو نيمهى يك روح، زن همزاد و دو پارهى يك واقعيت كه سابقاً ذكر شد از همين بينش آب مىخورند). به اعتقاد من عشق (مكملها) در واقع صورت خيالى نهاد خانواده و تقسيم كار اجتماعى بين زن خانهدار و مرد شاغل است و بردگى روحى ناشى از آن جزء مكمل بردگى اقتصادى زن مىباشد و عشق آزاد و برابر، اما پيوندى است كه دو فرد با هويت مجزا و مستقل وارد آن مىشوند و استقلال فردى و وابستگى عاطفى و جنسى فداى يكديگر نمىشوند.

بارى از ياد نبايد برد كه در ميان شعراى معروف معاصر به استثناى فروغ فرخزاد، شايد احمد شاملو تنها شاعرى باشد كه زنى با گوشت و پوست و هويت فردى به نام آيدا در شعرهاى او شخصيت هنرى مىيابد و داستان عشق شاملو و او الهامبخش يكى از بهترين مجموعههاى شعر معاصر ايران مىشود.

در شعر ديگران غالباً فقط مىتوان از عشقهاى خيالى و زنهاى اثيرى يا لكاته سراغ گرفت. در روزگارى كه به قول شاملو لبخند را بر لب جراحى مىكنند و عشق را به قناره مىكشند (ترانههاى كوچك غربت) چهرهنمايى عشق به يك زن واقعى در شعر او غنيمتى است.*

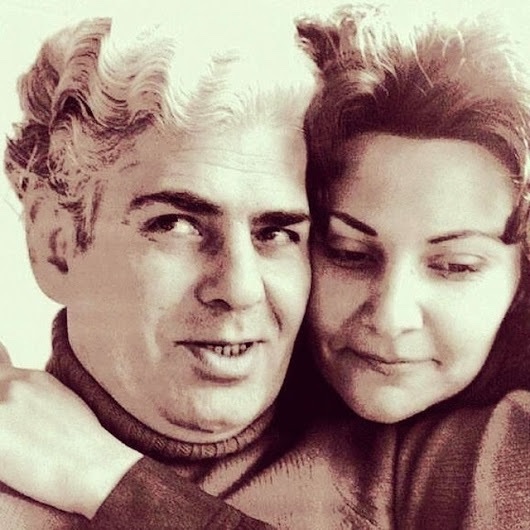

* این مقاله در هشتمين نشست «مركز مطالعات و تحقيقات ايران» در بركلى، آمريكا به تاريخ هشتم آوريل ۱۹۹۰ در حضور احمد شاملو و همسرش آیدا خوانده شد.

۲۴ ژوئيه ۲۰۰۰

https://iroon.com/irtn/blog/21607/

***

The Profile of Women in the Poetry of Ahmad Shamlu

By Majid Naficy

This is the 15th and last chapter of my book In Search of Joy: A Critique of Death-Oriented, Male-Dominated Culture in Iran (Baran publisher, Sweden, 1991).

This speech was first delivered at a conference sponsored by "Center for Iranian Research and Analysis" held in Berkeley, April 1990 in the presence of Ahmad Shamlu and his wife Aida Sarkisian. The Persian version of this speech had been published many times in different places, including my book Poetry and Politics and Twenty-Four other Essays [1].

In order to examine the profile of women in the poetry of one of the most influential modern Persian poets, Ahmad Shamlu (1925-2000) it is necessary to see him in relation to his predecessors. In our classical literature, woman has an absent presence, and perhaps the best way to see her figure is to demystify the mystical meaning of "love". Rumi (1207-73) divides "love into two mutually-exclusive parts: spiritual and carnal. A mystic man should cleanse himself from bodily pleasures and led by his master fills his heart with the love of God. In Rumi's poetry, Woman represents carnal infatuation or animal ego, and a mystic man should kill his temptations for this kind of deadly love: "Choose and love the living one who is eternal". On the contrary, in his lyrics Hafiz (born 1320) glorifies love for earthly beloved and uses "mystical love" only as a garnish. Nevertheless, Hafiz's earthly love is, also mostly non-physical.

The lover man is only a "gazer" staring at his beloved from her double chin upward. The beloved woman is not only deprived of physics but also any individual identity. Furthermore, this illusory woman is oppressor and bloodthirsty and like Afrasiab, the mythical king of Turan, who opened doors for the murder of his Iranian son-in-law, Sivash, sheds the blood of his beloved: "The king of Turan hears what my rivals say / Should be ashamed of the bloody injustice to Siavash". In reality, man is the oppressor and woman the oppressed but, in imagination, their roles are inverted because as psycho-analysts say, sadism and masochism are often interchangeable. [2]. With the emergence of modern Persian literature, woman shows her face and Rumi's spiritual love as well as Hafiz's earthly beloved are partially demystified. In his ballad, "Afsaneh" Nima Yushij (1896-1960), the founder of modern Persian poetry depicts a melancholy, but earthly love. His love has a concrete identity and belongs to a specific person and natural and social environment. A nomadic shepherd, filled with melancholy is sitting in a valley in Deilaman, near the Caspian Sea. He first describes a wild pear tree, a native lark and a wolf peeking out of a rock and then begins a dialogue with his heart which at the same time represents his beloved Afsaneh. Nima challenges the old bard, Hafiz from the tongue of this shepherd:

Oh, "hafiz! What is this lie and deception

That you put in the mouth of the cup bearer?

You cannot fool me if moan eternally

That you love only what remains eternal

No! I fall in love only with the fleeting [3]."

Building on this modern concept of love Shamlu begins to write his love poems. Inspired by a note that the poet himself had added to the fifth edition of his collection of poems, Fresh Air in 1976 [4], I divide Shamlu's love poetry into two periods: Roxana and Aida. The former is a historical figure and the latter the name of an Iranian-Armenian woman who married Shamlu in 1964. Roxana or Roshanak was the daughter of a Soghdian king whom Alexander, the Macedonian emperor married during his Persian campaign. In addition to a ballad, called "Roxana" which is written in 1950, Shamlu mentions the name of this woman directly or indirectly in some of his other poems in Fresh Air. He writes: "Roxana, a name which means "light" and "bright" represents an imaginary woman whose love brings light, freedom and hope. It took twelve years until such a woman found body and soul in my new collection of poems, Aida in the Mirror.. Before that time, this woman was a misty figure, fleeting and hard to catch, elixir and rare. Hopeless to find such a companion I wrote the poem "Roxana"." P. 348 In the poem, "Roxana", we are told of a man who lives in a wooden shack near the sea and the people call him a madman. He wants to join Roxana, the spirit of the sea, but she does not reciprocate his love:

"Let no one find out until the sun

Which must shine to the meadows and forests

Will finally dry out the waters of this separating sea

And put me on the sand as a beaten boat

Thus reunite my soul with Roxana,

The spirit of sea, love and life."

The unsuccessful lover who in the beginning of the poem remembers the past so bitterly:

"Let no one find out/ that I was stung / instead of being caressed or kissed" now at the end of the poem, sums up his unrequited love from the tongue of this misty woman as follows:

"And every one holds captive what one loves

And every woman locks her rolling pearl

In the confines of a little box"

In the poem, "Sonnet of the Last Isolation" dated 1952 we face the same hopelessness again:

"How could I be the harbinger

Of mankind and the whole world

When I have not found a love

Filled with light?"

In the poem, "Great Sonnet" dated 1951 Roxana is transformed into a "lunar woman", and the poet after calling her "the second half of my soul" writes in frustration:

“And there, in the starry horizon

Rises my lunar woman

With the sunny night of her eyes

In the purple blazes of pain.

Take me with you! Oh, the great knight of my white dreams!

Take me with you!"

In the poem, "Sonnet of the Last Isolation" the relationship between the poet and his imaginary beloved is compared to that of a child longing for love from a cruel mother:

"Something greater than all stars of all gods

It is the heart of a woman who can turn me into a child

Submissively hanging to her skirt,

Because for a long time I have been nothing but

A fearful loneliness chewed by the cold teeth of alienation

Shouting from the depth of my solitude.”

The other name of Roxana, this hypothetical woman is "Golku" whose name is mentioned in some of the poems of Fresh Air. The poet himself explains the word "Golku" as follows: "Golku is a name for girls which I've heard only one time in the villages of Gorgan, near Ali-Abad. One can accept that it should be pronounced "Golaku" the same way that the people of Shiraz pronounce the word "dokhtarku". But the pronunciation which I prefer and have used in one or two of my poems is "Golku" (which literally means "where is the flower?") pointing at a woman who could be an ideal lober or wife. At that time I thought that the suffix "ku" (where?) in the word "Golku" without necessarily signifying its usual literal meaning, could imply the absence and inaccessibility of the ideal woman." p. 345 Roxana and Golku are both imaginary women with this difference that the former is portrayed in a melancholic atmosphere, whereas the latter appears in social struggle supporting her revolutionary man. In the poem, "Fog" dated 1953 we read:

"I will reach home

Hidden in the cloak of fog

And surprise Golku.

She suddenly sees me at the doorway

With a drop of tears in her eyes

And a smile on her lips

She will say:

The desert is fully covered with fog

I was thinking to myself

If the fog would last until the morning

The brave men could return to visit their beloved ones"

The brave men should choose revolutionary struggle and welcome death like Abaee, a country teacher in Turkman Sahra, but girls such as Golku are advised to wait and only polish the weapon of Abaee's revenge.(Look at the poem, "From the Wound of Abaee's Heart" 1951) In another poem, "To Whom Your Love Is Life", dated 1951 we read about a war being fought between men and their enemies and the poet ask women to back men in their struggle. His tone resembles a classical Persian poet who in one of his proverbial verse, values women only for giving birth and raise "male lions":

"You, who have created epochs and centuries

And born men who had engraved epigraph

On their hanging scaffolds

And you carry the great history of our future

In your little wombs full of hope

And you have taught us endurance and strength

Against torture and pain."

Such women even owe their beauties to the astatic taste of men:

"You, who are beautiful

So that men praise beauty

And every man who follows a path

Is charmed by your sweet smile

And every man in his struggle for freedom

Is tied to the golden chain of your love"

Although women are called "the soul of life" but the actual protagonists are men:

"You, who are the soul of life

And the life without you is a cold hearth

You, whose songs of your embracing soul

Sound lively in the ears of men's souls

You who in the fearful journey of life

Have given peace to men inn your bosoms

And every self-worshipping man has worshipped you,

Give us your love

You whose love is life

And show your anger toward our enemies

You whose anger is death."

In the famous ballad, "Fairies" dated 1953 we see that the women of the tale, that is, the fairies, in the fight between the captured men and the demons have nothing to offer but daydreams, frailties and tears. In the collection of poems, The Garden of Mirrors, which was published [5] after Fresh Air and prior to Aida in the Mirror [6] and Moments and Ever [7], we find out that the poet is still looking for his "second-half of soul" and his "twin female". For example in the poem, "Punishment" dated 1955 he says:

"I do not find anything in women

Unless I discover my twin one day

In surprise and silence"

Finally this search bear fruit in Aida in the Mirror. In the poem, "The Fifth Hymn"written in the beginning of 1960's, the poet says to his beloved, "Aida: "You and I are two halves of one reality." Aida in the Mirror should be considered the best work of Ahmad Shamlu in poetry. In this volume one can no longer find exercises after Nima Yushij or French romantic writers and the poet has developed his own special style and diction. The language in these poems is simple and differs from an archaic tongue that Shamlu experiments in his later works influenced by the Persian prose writers of eleventh century like the historian, Abu al-Fazl bayhaqi (d. 1077). The poet regards the passion of his love as new source of his artistic creativity:

"Not in dream but in front of me

I see the creative years that I'll begin

My memory which is pregnant to a bountiful love

Multiplies the joy of becoming mother

In a long-delayed yawn.

You and your sincere passion

I and our home -

A table and a lamp.

Yes, in the deadliest moments of waiting

I pursue life in my dreams

In my dreams and my hopes."

(from "Song of the One Who Returns home from the Alley")

And A Longing" from the collection of poems Elegies of the Earth [8] in which he considers Aida's love as a new birth for him at age forty. Aida's love occurs at the time when the poet has become tired of "men and their odorous worlds" looking for a refuge in seclusion. In the poem, "The Road Beyond the Bridge" he says:

"I no longer want to travel

I no longer have a motivation

The train which is bellowing by our village at midnight

Does not diminish my sky

And the road which pass on the back of the bridge

Does not carry my desires

To the other horizons.

Men and their odorous worlds

Are a hellish book

Which I've memorized word by word

To find the high-reaching secret of isolation."

This love requires a return from city to the countryside, from society to nature. In the poem, "Aida in the Mirror", from which the book takes its name, we read:

"And your bosom

Is a small place for living

A small place for dying

And flight from the fraudulent city

Which shamelessly accuses the sky

Of impurity."

Also in the poem, "The Fifth Hymn" the poet writes:

"Our love is a village which never goes to sleep

Not at nights and not during the day,

And even for a moment

Movement, passion and life

Do not die away in it"

Now Roxana, the misty woman takes a human shape in Aida and becomes a real person. In the poem, "Hymn for Appreciation and Benediction" Shamlu says:

"Your kisses are chirping sparrows of the garden

And your breasts are the hives in the mountain."

And also in the poem, "Hymn of Intimacy" we read:

"Who are you that so trustfully

I would tell you my name,

Put my house key in your hand,

Share the bread of my happiness with you,

Sit down at your side

And go to sleep so gently

On your lap?"

Even the image of "night" that in Shamlu's previous poems (as well as his future works) was usually used as an allegory for "political coercion", now in this book regains its natural beauty and refers to the night itself. For example in the poem, "You and I, Tree and the Rain" in which the poet uses the language of folk songs we read:

"You are big like the night

In moonlight or no moonlight

You are big like the night

You are the moonlight itself

Yes, the moonlight itself

Even when the moonlight goes away and the night

Should go a long way to reach the morning gate

You are big and deep like the night

Yes, like the night."

Love for Aida reaches the apex of infatuation in the next Shamlu's collection of poems, Aida, Tree and Dagger and Memory [9] as seen in this poem:

"First I gazed at her for such a long time

Tthat when I took my gaze away from her

Everything in my whereabouts

Had turned into her figure

Then I understood that I have no escape

From her." ("Nocturnal")

However when the poet had to leave the countryside and come to the city, this infatuation diminishes and turns into companionship. Here Shamlu alludes to his pen-name, "Dawn"when referring to himself:

"And alas! That Dawn left the green valley

And regretfully returned to the city

Because in such a great era

One should go through hardship

To make ends meet

And save one's honor." ("Nocturnal")

In the above piece, the "great era" sarcastically refers to the "White Revolution" of the Shah which was supposed to bring equality and prosperity for the Iranian people in early 1960's. Subsequently Ahmad Shamlu comes out of his seclusion and his later collections of poetry, such as Blooming in the Fog [10]; Dagger in the Platter [11]; Abraham in the Fire; [12] The Humble Discoverers of Hemlock [13]; and Little Songs of Exile [14] demonstrate his attention to social issues especially the urban armed struggle of the leftist intellectuals in 1970's. In spite of the fact that in this decade, (contrary to the 40's and 50's during which the poem, "To Whom Your love Is Life" had been written) intellectual women play an independent and active role in social struggle Shamlu does not write any poem for these women, including Marziyeh Ahmadi-Oskooi who belongs to the same armed group which Ahmad Zeibaram does. Both of these individuals have heroically died and Shamlu writes a beautiful poem for the latter but not for the former.

The profile of women in the poetry of Ahmad Shamlu is gradually becoming unveiled from Roxana to Aida, but there are still some points of veil left. In Roxana, woman has an ethereal and intangible face lacking a real, personal identity. In other words, Shamlu in Roxana has not yet released himself from the illusory love in Rumi and Hafiz. Instead of recognizing woman as a human being with concrete flesh and soul, emotions, thoughts, actions and individuality and entitled to social rights equal to those of man, he portrays woman as a symbol representing abstract concepts such as love, hope and freedom. In Aida, woman is unveiled and the reader finds a real human being behind the figure of Ayda characterized with individual flesh and soul and identity. Here, love is a concrete experience and not a mystical illusion or melancholic imagination. This is exactly the paradigm which differentiates modern literature from medieval prose and verse, that is, turning to concrete and individual rather than abstract and generic, developing characters instead of typology.

Nevertheless, even in Aida in the Mirror we are not able to find an equal and free love between the two lovers. Shamlu looks for a shelter in this love, or as he says himself a "temple" ("The Road Beyond the Bridge") and a "mosque" (in Phoenix in the Rain [15]) and Aida is created only because she is the creator of this tranquility. Perhaps this love relationship is shaped by an approach toward sexual love between men and women that Shamlu has been attracted to from the time of writing poems for Roxana. According to this concept two lovers represent two "incomplete halves" who should join together in order to become a whole and complete unit. For example, the previously mentioned metaphors such as "two halves of one soul", "twin woman" and "two halves of one reality" stem from such a notion. In my opinion, the love theory of "the complemental pair" reflects an idealized form of the family institution and the social division of labor between the female housewife and the male breadwinner. The subsequent mental slavery of this love theory, in turn, facilitates the economic slavery of women. On the contrary, equal and free love requires a love relation between two individuals with independent and separate identity in which neither personal independance nor emotional/sexual dependance are compromised.

Nevertheless, we should not forget that among the well-known contemporary Iranian poets, with the exception of a woman, Forough Farokhzad (1935-67), perhaps Ahmad Shamlu is the only poet who in his poetry a real woman, lover, wife (by the name of Aida) is artistically portrayed, and the story of her love and Shamlu inspires the creation of one of the best collections of Persian modern poetry. In the poetry of the other poets, one usually finds "illusory love" and "ethereal" or "loose" women. In a country in which, as Shamlu says, "smile is amputated from lips" and "love is suspended from the ceiling" (in Little Songs of Exile) the artistic expression of love to a real woman should be regarded as a special gift.

(Persian text}

Notes

[1] Sh'er va Siasat va Bist o Chahr Maqaleh-ye digar, Baran publisher, Sweden, 1996.

[2]For further analysis look at my book in Persian Dar Jostojooy-e Shadi: Dar Naqd-e

Farhang-e Margparasti va Mardsalari dar Iran (In Search of Joy: A Critique of Death-Oriented

and Male-Dominated Culture in Iran), Baran publisher, Sweden, 1991.

[3] For further analysis look at my book Modernism and Ideology in Persian Literature:

A Return to Nature in the Poetry of Nima Yushij, University Press of America, 1979.

[4] Hava-ye Tazeh, Nil publisher, Tehran 1976. All quotations and poems by Ahmad

Shamlu mentioned in this essay are translated into English by me.

[5] Bagh-e Ayeneh, Tehran, 1960.

[6] Aida dar Ayeneh, Nil publisher, Tehran 1964.

[7] Lahzeh-ha va Hamisheh, Nil publisher, Tehran, 1964

[8] Marsiyeh-haye Khak, Amirkabir publisher, Tehran, 1969.

[9] Aida, Derakht o Khanjar o Khatereh, Nil publisher, Tehran, 1965.

[10] Shokoftan dar Meh, Zaman publisher, Tehran, 1970.

[11] Deshneh dar Dis, Zaman publisher, Tehran, 1973.

[12] Ibrahim dar Atash, Iran Zamin publisher, Tehran, 1977.

[13] Kashefan-e Forootan-e Shokaran, Azad publisher, Tehran, 1979.

[14] Taraneh-haya Koochek-e Ghorbat, Azad publisher, Tehran, 1979.

[15] Qoqnoos dar Baran, Nil publisher, Tehran, 1966.

***

لینکهای شعرها، مقالهها و کتابهای مجید نفیسی(بهفارسی وانگلیسی)

هیچ نظری موجود نیست:

ارسال یک نظر